Since I moved to the city, I’ve been dying piece by piece. It’s not really the smog, or the crowds, or my tiny apartment above the Arabic bookstore, or any of the things that bother most people. It’s the way people hurry around, their faces to the sidewalk, darting through the streets like ants swarming over a dead lizard. City life is fractured into thousands of pieces--faceted like the view from insect eyes. Maybe it makes sense to ants. To a small-town girl like me, it’s overwhelming.

The problem is that I’ve been here long enough to start dying. I lost two fingers last week. They fell off while I was sleeping. I found them next to my pillow in the morning, and put them in a shoebox with my big toe.

Riding home on the bus each night, I see other people who are dying. Not all of them are losing body parts like I am. There’s one guy, an old man who shaves badly--looks like a war vet or maybe an ex-cop. He smells like mothballs. He’s got a patch of dead gray skin on his cheek. It looks like frostbite. It’s spreading; yesterday it stretched across his broad nose. There’s a girl about my age with blood dripping from her ears. I try not to sit by her because she bleeds on the bus seats. There’s a black drag queen who’s fading. Last time I saw her, she was nearly transparent. The streetlights flickered behind her as we rode together. She caught my gaze and winked with a diamond-edged eyelid, then got off at the next stop. I haven’t seen her since. I think she’s gone.

One Friday night, after I’d been working late typing up a deposition, I took a later bus than usual. When I got on, the driver stared at me with empty sockets. His eyes had rotted away. But his hands and feet remembered the route, and they controlled the steering wheel and gas pedal. I sat in the handicapped seats so I could watch him. The bus crept through city traffic, so slowly it couldn’t hurt anyone. Traffic signals turned green for us, and stayed that way for three minutes as we crossed the intersection. It was on this bus--watching this driver--that I realized if I stayed in the city I’d lose myself completely.

When I got home, I raced up the outside steps. I caught my boot on the metal stairs as I fumbled my keys out. Kicking the stairs, I pushed the key at the door. The sound of a power drill caught my attention. I glanced across the landing at the other apartment above the bookstore. I hadn’t met my neighbor, but I’d seen the guy--tall, shaggy-haired, usually covered in paint. An artist, for sure. This city was full of them.

As I set my purse on the kitchen counter, I heard a knock on the door. I remembered my big-city training: don’t open the door, not in the city. You’re not in a small town now. Through the peephole I saw the artist from next door. He was standing on the porch we shared, his hand raised to knock again. I opened the door.

He was taller than I’d realized--well over six feet. His hair was curly and wild, sort of ginger-colored. He wore a Free Tibet tie-dye shirt with a green streak across the front, like he’d wiped a hand there once. He was picking at something on his hands. “Hi,” he said. “I’m your neighbor.”

“I know,” I said. I extended my right hand.

“I’m Trent. I’d shake your hand, but I’ve got glue on mine.”

He was whole, with nothing dead that I could see on him. I wondered how long he’d been here. “Julie,” I said, tucking my left hand behind my back. I didn’t want him to see the missing fingers.

“Listen, I was wondering... could I borrow a cup of something? One cup.”

“Of...?” I figured I’d misheard him. “Of what? Sunshine? Roaches?”

“Oh, brown sugar, I guess.”

I noticed his eyes were pale green and large, like a frog’s. “Sure,” I said, turning toward the kitchen. It was the kind of request that neighbors made all the time, where I was from. Too late I realized I shouldn’t leave the door open behind me, in case he meant some sort of harm. Too many years in a small town; all the ways of being in the city were foreign to me. They were things I’d learned from brochures, travel guides, the Internet. All the ways to keep the city off me, to stop it from hurting me.

“Thanks. You’re awesome,” he said.

I pulled a plastic measuring cup off its ring and packed it with brown sugar. He watched me carefully. I saw his eyes shift toward my bad hand. “Here you go,” I said, offering him the sugar.

“Can I keep the cup?”

I paused. “My measuring cup?”

“Yeah. Can I have it?”

“You gonna buy me a new one?”

“No,” he said, “but I’ll tell you why your fingers fell off, and why half this city is dying.”

I looked at him, outlined by my doorframe and the cement wall behind him. “Okay,” I said. “Keep it.”

“Thanks,” he said, walking across the porch.

I stepped outside. “Wait, you said you were going to explain it.”

“I will,” he said as he opened his door and stepped inside. “Come over tomorrow morning and I’ll show you.”

That night, I lost my hair. It lay on my pillow in the morning, long and straight and pale, like dead grass. I picked it up and tied a black ribbon around one end, then put it in the box with the other things I’d lost. I looked at myself in the mirror, thinking I looked like a cancer patient. I had to get out of the city. I’d start packing tomorrow afternoon.

First thing in the morning, I knocked on Trent’s door. The cold night-time winds were still blowing, and it was only day because the sun was up. An orange leaf fluttered past my face. I pulled my jacket closer to me, feeling the wind on my bare head.

Trent opened the door. He was still wearing the same shirt, and I wondered if he’d slept in it or just stayed up all night. His apartment smelled like patchouli. His eyes flickered over my head, but he just said, “Julie. Come on in.”

I stepped through the doorway into a chaotic front room. The walls were covered with peculiar painted items--large-nosed dolphins, giant paper carrots, portraits of impossibly-built people. In the corner stood a plush green couch with fish-shaped pillows. A nearby end table had five legs, each bent at a similar angle, skewing the table sideways. There were no books, no TV, no stereo. Nothing to show that time was spent here; only the result of time, which was artwork.

He saw me looking around. “Sorry,” he said, “This room doesn’t get cleaned much. I stay in the bedroom mostly. I wanted you to meet her.”

“Who?”

“I don’t think I can explain. Just come see.”

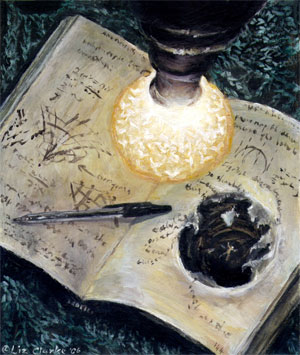

I followed him past the kitchen nook and the small half-bathroom into the bedroom. The room was dark. In the light from the hallway, I saw stacks of paint cans, power tools, tubes, and various junk items I couldn’t identify. They were piled in the corners, making the place look like one of the crazy-old-cat-lady rooms--the places where they hoard Social Security stubs and empty Tupperwares until someone calls about the smell. But this room smelled more like paint thinner than anything else, and I suspected Trent could find anything he needed without a moment’s thought.

Trent pushed through the dark room. “Hang on, I’ll get the light. It’s on the wrong side of the room. Cheaply built, you know. Haven’t had a chance to rewire it.”

My eyes were adjusting to the dark when the light came on, fluorescent and awkward. I blinked a few times before I saw her. She was shining in the light before me, a body built of metal and plastic and paint and wood, and assembled with love. She was shaped like a woman, but composed of thousands of different pieces: bus tokens, pencils, paper bags, everything I could think of. For a moment I thought it was trash, but then I realized that every part of her was in good condition, and some things weren’t what people would have thrown away--like the hundred-dollar bill papier-mâchéd to her neck. She had a remote control in one of her feet, and a well-polished antique table leg for a spine. Part of her left breast was my measuring cup, the one I’d given him last night. Her eyes were sparkling gemstones, one brown and one blue. She was pieces of everything, and yet whole unto herself.

She reclined on the bed, on a red quilt like an empress. She was beautiful, and I found myself feeling more alive than I had since I came to the city.

“Her name is Galatea,” he said, moving towards me. “After Pygmalion’s sculpture.”

“She’s incredible,” I whispered, reaching a hand forward. I paused. “May I?”

“Please,” he said. “She’s meant for touching.”

I touched her, only noticing after I’d done it that I’d used my damaged left hand. I withdrew it carefully. “Did you build her all by yourself?” I envisioned her coming to life with a kiss, embracing her creator. I glanced at Trent, imagining Galatea’s body wrapped around his, in a tangle of metal with tie-dye.

“That’s the thing,” he said, sitting down heavily on the bed. “I didn’t build her.”

“That’s the thing,” he said, sitting down heavily on the bed. “I didn’t build her.”

I felt myself cooling off, like someone had dumped water on my head. “Oh,” I said. “So you bought her like this. At an art show?”

“No,” he said sharply, “I built her in that sense. I added every nail, every drop of glue, every touch of paint--all by myself. She’s all my artwork, every piece of her.”

“Sorry,” I said, and meant it. “I just thought--”

“No, I assure you she’s my project. I wanted to build a sculpture made of objects I had to persuade someone to give me. All things from this city.” Trent sighed and rubbed his temples. “I mean I didn’t build her. I think she built me.”

I looked at him, his wild hair sticking up like a scrub-brush, and thought for a moment he’d gone insane. A crazy artist, talking to his projects. “How could she build you?”

“Originally, I added everything I got from people. I tried to be as outrageous as I could, seeing what people would give me. There’s actually an expired security badge from the Pentagon buried inside her. And a placenta--dried out, of course--and a 1900 penny that’s worth a lot of money, or it was until I glued it to a doll’s head and stuck it in her stomach. But sometime after I’d built her torso and head... that was probably six months ago or so. Sometime around then, she started rejecting parts.”

“What?”

“You’re going to think I’m crazy,” he said apologetically, and with those words and the way he said them, I felt embarrassed for having thought it. “But yeah. She rejected them. I’d glue something down at night, and then in the morning when I came back, the piece wouldn’t be attached. It was like I’d never stuck it down. Sometimes I’d even find a piece on the floor, like it had been cast off or something. It creeped me out. I hooked up a webcam to try and watch it, but there was nothing. The picture was blank no matter what I did with it.”

I ran my hand over my bare scalp, marveling at the way I could feel the texture of my fingers. “And she built you?”

“She’s certainly trained me to bring her what she needs,” he said.

“What does this have to do with my lost fingers?”

Trent stood up and walked to the window. He looked out at the grayness and tapped his fingers on the glass. A few leaves fluttered across the sky. “It’s just a theory, now. I don’t know more than you do.”

I wove my fingers together and stared at the gap they created. “Okay. A theory’s more than I’ve got.”

He turned and looked at me. “I think this city is like that too.”

“Like what?”

“Building itself. Making itself into what it wants to be.”

I looked at him. “The way Galatea builds herself?”

“Yeah. The city chooses what it wants to be here, and what it doesn’t. If it accepts something, it cements it in so deeply that sometimes it gets lost there, like the 1900 penny. If it rejects something--I had this girlfriend once--” He didn’t finish the thought.

I sat down on the bed next to Galatea. “You think the city rejected me?”

“Are you happy here?”

I shook my head. The pit of my stomach ached. “Maybe you’re right. It doesn’t matter--I’m leaving. I decided that last night. I’m leaving before I lose anything else.”

He sighed. “I’m not sure it’ll help. I don’t know, but...”

I stared at him. I wanted to scream, but no one but Trent would hear. The sun moved from behind a cloud and lit the room, incongruous with the despair I felt. “So what can I do?”

“I don’t know,” he said. “I don’t know why it happens or what to do. I just see it.”

“I don’t want to leave. I want to belong. But I don’t know how.”

“It’s not something to know,” he said. “It’s just something you do. Something you are.”

“Maybe I can become someone else,” I said. “That’s what I wanted to do when I got here. I didn’t really want to come, but I’m a first-gen college grad. My mom said I should come here. She said I was too smart for the town I was in--I needed to be somewhere where I could help people, and do something with myself.” I shook my head. “It’s a lot of pressure. Everyone’s counting on me to become someone.”

“Maybe that’s why you’re dying,” he said gently. “Because you wanted to be someone else.”

I didn’t answer. I was thinking of my hometown, where I wasn’t afraid. Trent sat down next to me. “Sometimes when I try to put something on Galatea, I just need to find the right spot. Sometimes she rejects something just because I placed it wrong. Maybe you need to find where you fit.”

“Maybe,” I echoed. I imagined myself as a piece of this city, a small bit of scrap to something so massive. “I’m scared, Trent.”

“Me too. I’m frightened all the time by the things I see around me.”

“What do you do?”

“The same things I’d do if I weren’t.”

That afternoon, I went for a walk to the tiny park I’d never visited before. It was just one city block--with a low fence, a dozen trees, and a picnic bench. There was a wire garbage can, where someone had tossed a stack of old magazines and a broken broom. I threw my granola bar wrapper away, sat on the picnic bench, and tried to remember who I’d been before I came to this city.

I was generous, I remembered--I always made time for friends and family. I threw a surprise birthday party for my mom, just before I came here. I spent hours making paper decorations, to save some money. It had all been worth it, to hear my mom’s laughter when she saw all her friends together in the same place. When was the last time I’d called my mom? I couldn’t remember. I’d done it regularly when I’d gotten here, but I’d fallen out of the habit. I was trusting; I never locked a door, not until I moved here. At home I liked to talk to the mail carrier and ask about what she’d seen lately. But in the city I had to build these walls, to keep danger out.

I glanced down at my feet, where the maples had dropped their helicopter seeds into a brown carpet. I picked one up and threw it in the air. It spun around and fluttered slowly to the ground. I scooped up a handful and threw them, watching the wind take them into a pile of maple leaves someone had raked nearby.

I glanced down at my feet, where the maples had dropped their helicopter seeds into a brown carpet. I picked one up and threw it in the air. It spun around and fluttered slowly to the ground. I scooped up a handful and threw them, watching the wind take them into a pile of maple leaves someone had raked nearby.

If the city was rejecting me, then either I had to find where I fit or just give up. And I didn’t want to just give up.

I stood up from the park bench and my right leg remained behind. I glanced down at it curiously. The leg remained bent at the knee, as if my body were still attached. It could have been a sculpture there, a stray leg piece someone had left as design. There was no blood, just a cauterized stump at my hip. I looked at the stump, feeling a phantom sensation of having a leg there. I shivered and felt my armpits sweating. Fear rushed through me, like blood in my veins, pushing toward the limb that it could no longer reach. I saw myself scattered across this city, with no core left to me at all. I had to make the city accept me--to believe that I belonged here.

I fished the broken broom out of the garbage to use as a crutch. My granola bar wrapper fluttered to the ground and into the pile of maple leaves. I called a cab to take me home, and then I knocked on Trent’s door.

I didn’t see him at first. I looked over the balcony’s edge and saw him standing in front of the bookstore, talking to the owner. I’d never spoken to the man--he was very tall, and always felt threatening to me. The man handed Trent a brown headscarf and said something in Arabic. Trent smiled and repeated the words back to him, slowly and poorly accented. The owner laughed. I watched them clasp hands, then embrace briefly, their left hands on each other’s shoulders. The owner went back inside. Trent glanced toward his door and saw me, leaning on my crutch, and his face went sober.

He came upstairs, helped me inside, and poured me a glass of Coke. I sat on the green couch and studied the fish pillow. He’d painted it to look like a rainbow trout.

“How much time do I have, Trent? How long do I have to stop this?”

He held the glass out to me. The ice crackled in the carbonation. “I don’t know,” he said. “You’re being rejected so quickly.”

I took the Coke, drank some, and set the glass on the end table. A thought occurred to me. “When will I lose consciousness? Can my head fall off? Or is it when my torso falls off? I don’t know which one falls off from the other.”

“I don’t know either.”

I laughed, because it was less painful than thinking about what was happening. “Maybe I can do something to appease the city, like a sacrifice to an angry god or something. I saw people kill pigs when I was growing up. I could manage, if someone held the pig down.”

“My girlfriend tried planting flowers along Main Street,” Trent said as he sat down next to me. “To make the city look nicer. Before she--well.”

The thought was like an ice cube pressing on my heart. “I guess that’s not enough, then.”

“I don’t know. I don’t know at all, Julie. I’m so sorry.”

I reached for the Coke and grasped the glass in my hand. “There’s got to be something I can do. I’m not going to give up. I have too many people counting on me, even if none of them are here right now.” I took a deep breath. “I wish I’d gotten to know you more in the last few months. I was kind of hiding in my apartment.”

“A lot of people do that when they’re new in a city,” said Trent. “They’re scared. Afraid to make connections and set down roots, when they’re not sure they’re staying.” He paused and looked at me. “Do you feel scared now?”

“Not really,” I said. “Well, yeah. A bit. I’m scared of dying. Who isn’t?”

“Galatea,” he said.

Neither of us said anything for a minute. I tried to bring the Coke to my lips again, but I realized my arm wasn’t responding. I glanced to my left. My hand held the glass. My arm rested on the side of the couch, separated from my shoulder.

My toes curled up inside my boot, and I gritted my teeth. I looked at Trent. His eyes were wet as he took my hand. The pressure of his grip was comforting. “Julie,” he said, his voice wavering.

“I want to fight this thing. I want to make the city understand that I belong here. I may be from a small town, but that doesn’t mean the city gets to kill me. I’m not going to let it, Trent. I won’t.”

Even if I wanted to fight, I couldn’t move on my own anymore--not very easily. It’s hard to fight something you can’t see, especially when it strips away your body. All that’s left is your mind, and you have to hope that’s enough.

Trent carried me back to the bedroom and lay me down next to Galatea. “I’m sorry, Julie,” he said as he wrapped the brown scarf on Galatea’s head. “I wish I could do more.”

“You’re doing a lot,” I said. “Just being here.” It was true; this was the most human contact I’d had in months.

He paused at the door. “Do you need anything more?”

“Got any glue strong enough to fix me?”

He smiled a bit. “I wish. Anything I can do to help you?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Do you want me to stay?”

I thought about it, but said, “No. I’d rather have some space, but thanks. This is my fight. I’ve got to do it on my own. But... it helps, knowing you’re nearby. It helps a lot.”

I felt like Trent understood what I meant, even if I couldn’t say it. I would have known him in my hometown--would have known everything about him, and all his secrets. I was surprised to realize that here I hadn’t even tried. Trent nodded. “I haven’t slept all night. I was napping on the couch when you knocked earlier. I think I’ll nap again.”

“Okay.”

“I’m a light sleeper. Call if you need something?”

“Yeah.”

He stepped into the living room. After a moment, I heard him snoring. Restlessly, I looked at Galatea. She was tilted slightly towards me, her eyes glinting in the gray light from the window. I watched her for what seemed like hours, although it was probably only minutes.

I tried imagination; I visualized the city accepting me as part of itself. I tried reason, by listing all of my best qualities I could give the city if it’d let me.

How do you fight something you can’t touch?

I felt my body changing; my ears fell off, which stopped the sound of snoring. My right arm separated at some point, and lay solemnly next to me on the bed, like a spray of flowers at a funeral. I was afraid, but I fought it down.

“Galatea,” I whispered, “Where do I go when this is done?”

She didn’t answer. Or if she did, I couldn’t hear her. She lay silently next me, a collection of pieces that had become her own. The light through the window shifted from afternoon to evening, then into twilight. Trent hadn’t returned. I felt cold, but couldn’t shiver. I was falling into pieces, into isolated fragments, just like the city itself.

Just like the city. I wondered if I could convince the city I loved it. I tried to view my childhood in fragments, like an outsider would see it. A certain crack in the sidewalk, a silent layer of snow on the trees, the way the town’s only traffic light became colored stripes when you squinted at it. These were all things I could find in the city too. Why were they connected at home, but fragmented here?

Maybe my job was the problem. I could find a different job, something where I felt like I was helping people. Something where I could talk to people. I went to school to be a paralegal; maybe I could volunteer somewhere in the evenings. Maybe I could do something for the war vets who were suffering, or the drag queens, or someone else. Can you hear me? I asked the city. Do you see that I’m trying?

I couldn’t tell if the city understood me. Galatea watched me with a steady gaze. She was eclectic and strange, yet familiar. I wondered who’d given Trent the yo-yo for her shoulder, the eraser for her nipple. The last light passed through the room, shining across Galatea’s figure. I blinked, and my eyes fell out.

“I can’t see,” I whispered in the darkness, and then shouted. “I can’t see!”

In a moment I felt Trent’s hands stroking my cheeks. His fingers were calloused, and rough with dried glue. Without my eyes and ears, all I could do was feel; the heat of Trent’s fingers warmed my skin. He smelled like oil paints and iron tools. I wanted to touch him, to hold onto the only connection I had, but my hands were gone. I extended my tongue, letting it slide against the knots of his knuckles, tasting the chemicals of creation on his skin.

The taste changes me. I can only feel each finger where it touches me, but I know those fingers connect to a hand, which is part of Trent. The fragments of my life touch those of the people around me--if I let them, if I open up to them. Trent was right. There’s nothing to fight.

I open my faceted eyes--one brown, one blue. I feel the 1900 penny inside me, pressed against a doll’s head. I am the drag queen, the war vet, the girl who bleeds from her ears. I embrace them as I embrace myself, my creator, my creation. I stretch from the bed, reaching for Trent as I reach for anyone who dreams, anyone who has hopes in this city. I press my whole body against him, feeling him for the first time. He welcomes me with warmth against the measuring cup of my breast. I have never been alone.

“Do you see now?” asks Galatea, the city, my companion in this body.

Yes. I do.

“That’s the thing,” he said, sitting down heavily on the bed. “I didn’t build her.”

“That’s the thing,” he said, sitting down heavily on the bed. “I didn’t build her.” I glanced down at my feet, where the maples had dropped their helicopter seeds into a brown carpet. I picked one up and threw it in the air. It spun around and fluttered slowly to the ground. I scooped up a handful and threw them, watching the wind take them into a pile of maple leaves someone had raked nearby.

I glanced down at my feet, where the maples had dropped their helicopter seeds into a brown carpet. I picked one up and threw it in the air. It spun around and fluttered slowly to the ground. I scooped up a handful and threw them, watching the wind take them into a pile of maple leaves someone had raked nearby.